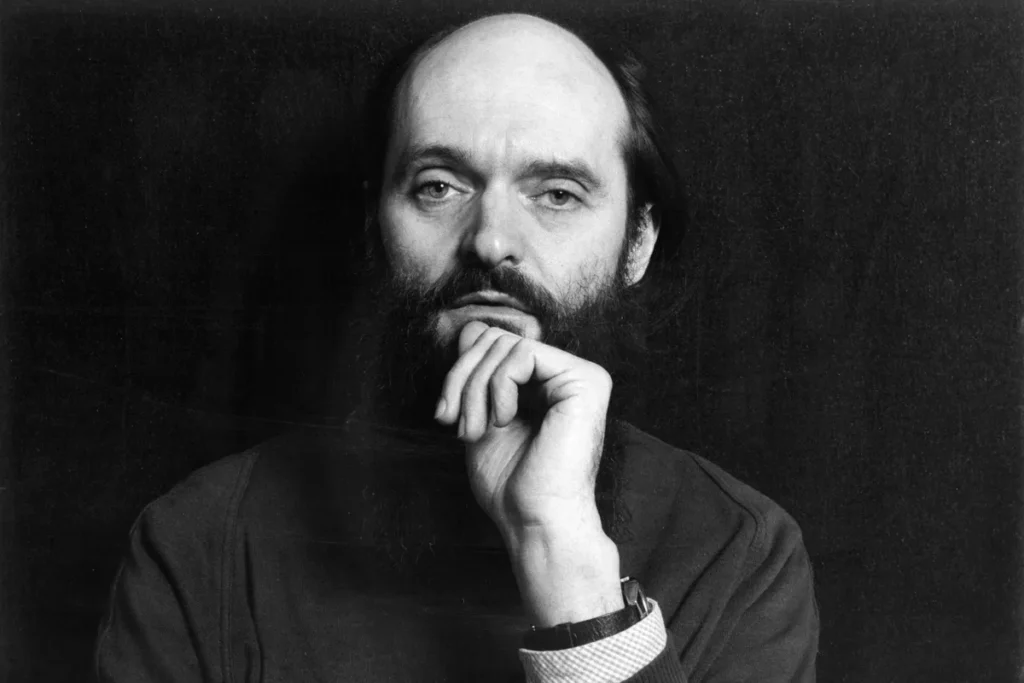

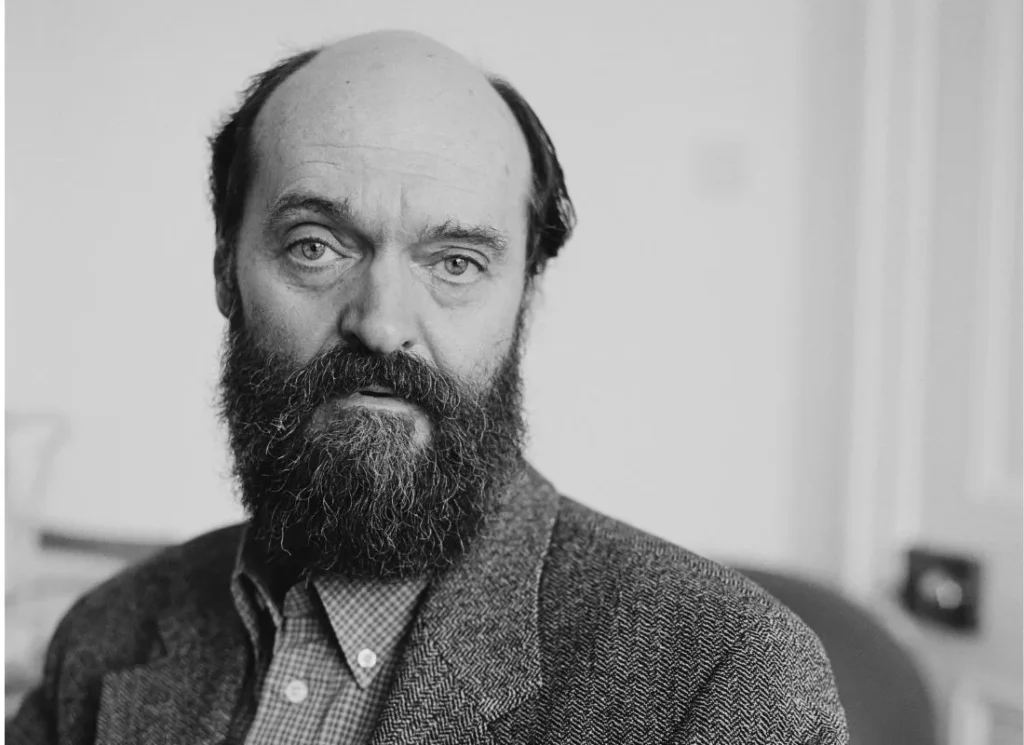

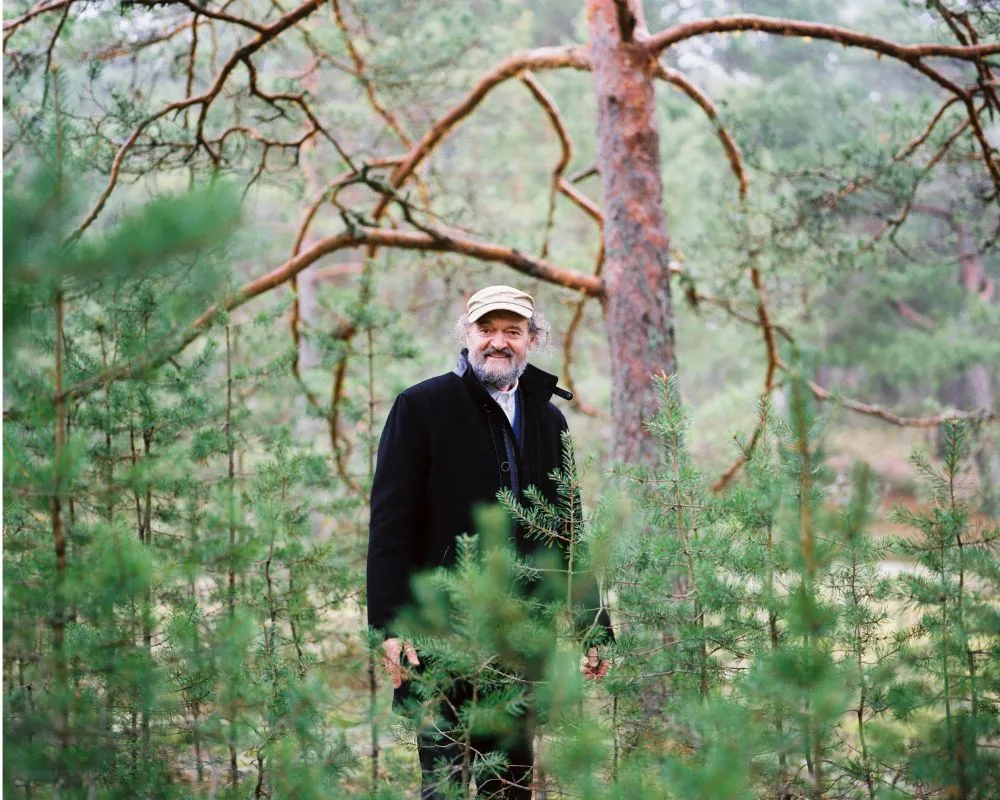

artLIVE – Arvo Pärt’s music is a contemporary Estonian pioneer. In a noisy and complex world, he writes prayer-like melodies – minimalist yet profound.

Translated from BBC Music Magazine | April 8, 2025

Author: Peter Quinn

Arvo Pärt’s music is steeped in a world of luminous silence, where every note is sacred and intentional.

With his signature “tintinnabuli” style (like the chimes), his compositions combine ancient tones with modern minimalism, evoking deep spiritual resonances. In a noisy and chaotic world, Pärt’s music is a rare respite – pure, clean and contemplative.

A sound so unique it needed its own label

Not many composers can inspire a label to be created just to record their work, but that’s exactly the case with Arvo Pärt. When he heard his minimalist and meditative melodies on the radio, Manfred Eicher – founder of ECM in Munich (Germany) – decided to open a new branch called ECM New Series in 1984. Since then, Pärt has not only established himself as one of the most unique voices in contemporary music, but has also become one of the most performed and recorded composers in the world.

Born on September 11, 1935 in town Paide, Estonia, Arvo Pärt studied composition at the Tallinn Conservatory under the guidance of Heino Eller – one of his most influential teachers. Although his current status is almost entirely linked to the works he composed since he introduced the tintinnabuli style in 1976, starting with the crystal-clear beauty of the piano piece Für Alina, during the 1960s Pärt was known as something of an “eccentric” in Soviet music circles.

Listen to Für Alina – The silences carry emotion and weight in each note.

Pärt’s first mature work, the dark and expressive Nekrolog symphony (1960) – also the first Estonian work to adopt 12-tone serialism (serialism). This earned him harsh criticism from the all-powerful head of the Union of Soviet Composers – Tikhon Khrennikov, at the Third All-Union Congress of Composers held in Moscow in March 1962.

Playing with music

While sequential techniques were the basis for much of Pärt’s work in the 1960s, it seems that his real passion was the play between numbers and pitch sequences – an element that would later become characteristic of his tintinnabuli style. Rather than confining himself to serialism, Pärt used other avant-garde techniques such as pointillism and aleatoricism. He produced a series of experimental works such as Perpetuum Mobile (1963, dedicated to composer Luigi Nono), Symphony No. 1 (1964), Diagrams (1964) and Musica Sillabica (1964).

In all these experimental works, the extremes of dynamics and texture are sometimes pushed to such extremes that the music seems to be on the verge of collapse. Increasingly dissatisfied with serial technique, Pärt began to explore new avenues for his compositional practice, including the incorporation of “borrowed” tonal gestures (particularly from Bach), as well as the application of Baroque and Classical musical forms.

A playful, inventive spirit is always present

In Pärt’s works from the mid- to late 1960s, a playful, inventive spirit is always present. Consider the humour of the musical “catchphrase” that brings Quintettino (1964) to an ambiguous conclusion; Or in Collage on B-A-C-H (1964), Pärt quotes Bach’s Sarabande from English Suite No. 6 in the central movement of Collage on B-A-C-H (1964), but then distorts it to an almost grotesque extent.

The Silent Years

After the remarkable Credo (1968) – a work that marked the culmination of his early writing period and the first time Pärt wrote music on the basis of religious texts – he fell into a crisis and entered a period of silence that lasted for many years.

And then, after a fateful encounter with Western hymns, Pärt was reborn creatively. He was absorbed in the study of medieval and Renaissance music, and converted to Russian Orthodoxy (he had previously been a Lutheran). Inspired by ancient hymns and music, Pärt completely changed his style, stripping away and restructuring all his musical ideas and techniques.

It was not until 1976 that Pärt found – intuitively – the tintinnabuli style that would become his signature. At the heart of this style is a two-part structure: a melodic line that moves step by step, accompanied by a triadic layer of harmony called tintinnabuli – the name comes from the Latin tintinnabulum, meaning “little bell”.

1977: A Creative Rebirth

A series of works began to flow in 1977 – the year that has been called Arvo Pärt’s annus mirabilis (miracle year). Among them stand out three works that have become symbols of the new style: the enchanting Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten, the absolutely structured Tabula Rasa concerto for two violins; and the circular loops of Fratres. What is most impressive about this trio is that each piece possesses a distinctly self-contained concept and a completely unique sound world. The core of their aesthetic effect is the sequential implementation of the musical process, in which each musical parameter is the result of strict adherence to a pre-determined formula.

The most complete expression of the tintinnabuli style appears in the St John Passion (1977/1982). With the ambition to become a musical vehicle, Pärt decided from the beginning that the entire content of the work would be drawn from the biblical text itself. He did this by setting each syllable to music precisely, with the sentence structure, note length, and pauses between phrases all strictly following the punctuation of the original text. The result is a work of extraordinary focus and restraint, at once detached and deeply affecting.

As Pärt himself has said, the language of the text is the factor that shapes almost the entire distinctive character of each vocal work. From the beginning he worked mainly with Latin texts, but in recent commissions he has expanded into Italian in the “mini-cantata” Dopo la vittoria (1996), and Spanish in the psalmody Como cierva sedienta (1998).

There are also quite a few works written in English, such as Litany (1994), with its liturgical style of praise and response; I Am the True Vine (1996), which returns to the Gospel of John, written to celebrate the 900th anniversary of the founding of Norwich Cathedral; and Littlemore Tractus (2001), commemorating the birth of Cardinal John Henry Newman.

Of particular significance is Pärt’s choice of Church Slavonic, an ancient language used only in liturgical texts, to set to music the short Bogoróditse Dyévo (1990) and the epic Kanon Pokajanen (1997). Both are testament to the remarkable versatility of the tintinnabuli style. The sound world they create is reminiscent of the illustrious tradition of Russian Orthodox music, although in fact they are composed according to the same rules as all of Pärt’s other tintinnabuli works.

Pärt’s music does not speak; it listens

Arvo Pärt’s unique contribution to contemporary music lies in his ability to reconcile modern minimalism with the spiritualism of early music. His simple yet emotionally charged tintinnabuli style invites the listener into a meditative experience that transcends all aesthetic trends.

Pärt’s music does not speak; it listens, waits, and unfolds. In an age dominated by speed and complexity, his works offer a valuable counterpoint – an art of introspection, patience and restraint. Through minimalist structures and a clear mind, Arvo Pärt not only redefined religious music, but also created a universal language of silence and sincerity.

Photo: Getty Images