artLIVE – Forget the dazzling opulence of Rome for a moment. Here in the heart of the city, you’ll encounter raw, unvarnished masterpieces, works that lay bare the harshest truths of Caravaggio’s world of painting.

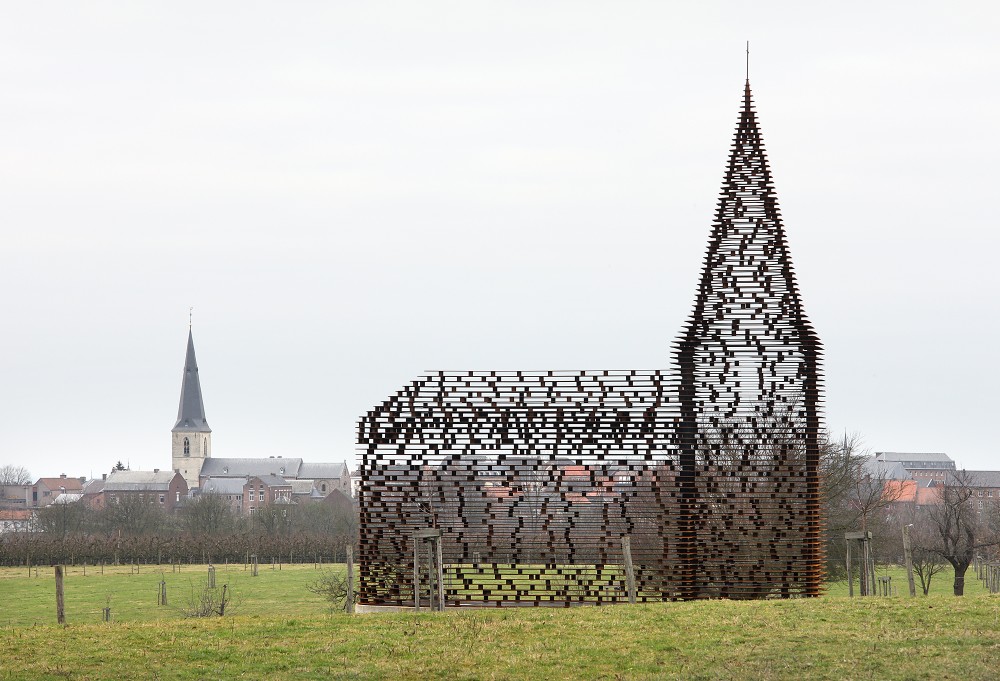

Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1601)

Caravaggio’s Conversion on the Way to Damascus was commissioned by Tiberio Cerasi – a Roman jurist and Treasurer-General to Pope Clement VIII. The painting captures a pivotal moment from the Bible: St. Paul, once a fierce opponent of God, is struck by a divine light on his journey to Damascus (Syria). This holy illumination throws him from his horse, blinds him, and sets him on a path of profound conversion, the beginning of his transformation into one of Christianity’s greatest apostles.

In the painting, St. Paul lies motionless on the ground, his body contorted, arms flung wide as if overwhelmed by the celestial light. Beside him, a horse dominates the canvas, standing calm and unmoved by the miraculous event. The horse’s handler, too, appears indifferent, quietly holding the reins – a detail that heightens St. Paul’s isolation in this moment of divine revelation.

Notably, Caravaggio depicts St. Paul wearing ancient Roman armor rather than contemporary clothing – a deliberate choice that lifts the figure out of a fixed historical moment, emphasizing the symbolic power and timeless resonance of this awakening of faith.

With his bold realism, dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, and unflinching portrayal, Caravaggio presents the miracle not as a mystical spectacle but as a profound spiritual upheaval moment that lays bare human solitude and fragility in the face of divine truth.

The Calling of St. Matthew (1599–1600)

The Calling of St. Matthew is part of a trilogy of paintings about St. Matthew that Caravaggio created for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome. The work captures the life-changing moment when Matthew is called by Jesus to follow Him.

In a dimly lit room, Jesus enters and points directly toward a group of men gathered around a table. Scholars believe that the bearded man, pointing to himself with a look of astonishment as if to ask, “Me?” is Matthew.

A shaft of light slants across the canvas, illuminating St. Matthew, a symbol of divine grace and the moment of spiritual awakening when one realizes they are called.

Pope Francis has shared that, as a young man, he often visited the chapel simply to contemplate this masterpiece. The two other works in the trilogy, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew and St. Matthew and the Angel, are still displayed alongside it.

Madonna of Loreto (1604–1606)

Caravaggio’s Madonna di Loreto is a vivid testament to how he broke with traditional conventions of religious art in his time.

In the painting, the Virgin Mary appears simple and approachable, standing barefoot at the threshold of an ordinary house, bathed in a warm, gentle light. The only sign of her divinity is a faint halo above her head, evoking both humility and sacred dignity.

In the foreground, two kneeling pilgrims are depicted in humble clothing, their faces weary, their bare feet soiled. These were images that religious art of the time typically avoided, yet Caravaggio chose to highlight them: hands clasped tightly in prayer, face lifted toward the Virgin with deep reverence and hope. The result is a faith that feels genuine, unadorned, and without grandeur.

When first unveiled, the painting shocked the public with its raw, bold portrayal, so starkly at odds with the idealized style common in religious art.

Today, however, Madonna di Loreto is celebrated for its profound humanity. Caravaggio affirmed that faith is not found in distant, otherworldly ideals, but in the eyes, hands, and feet of ordinary people, the very people the Church is called to serve and stand beside.

Rest of the Flight into Egypt (1597)

In his first large-scale religious work, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Caravaggio created a scene that is both sacred and lyrical: an angel quietly plays the violin, offering a gentle lullaby for the sleeping Virgin and the Christ Child. The angel’s wings are barely visible, evoking the image of Orpheus, the poet of Greek mythology who moved both nature and the divine with his music.

Though the main figures bear an idealized grace, Caravaggio subtly adds a tender, earthly detail: the donkey standing nearby, its eyes brimming with tears, a quiet reminder that even in the realm of the divine, there is room for the simplest human emotions.

The surrounding scene is a silent, dreamlike meadow. Unlike his usual restraint, here Caravaggio lets his brush flow freely: tangled leaves, flowing drapery, and soft fabrics that seem to stir in the breeze, all creating a space filled with poetry and a sense of boundless freedom.

This painting is not merely a sacred tableau; it is a profound allegory of music. It is as if Caravaggio whispers that music nourishes the soul, a fragile yet enduring bridge that connects humanity to the divine, beyond words and reason.

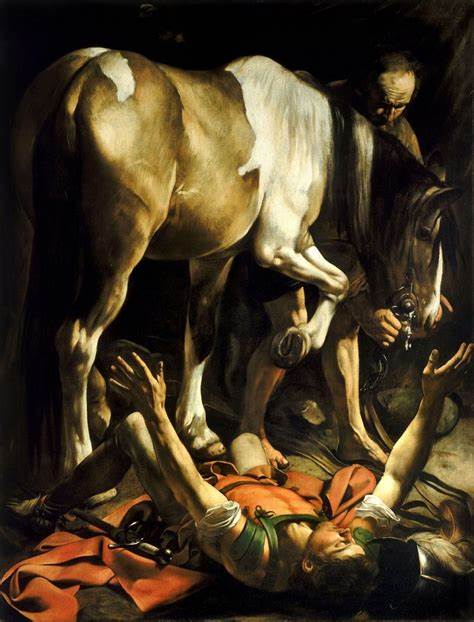

St. Jerome Writing (1606)

Caravaggio’s St. Jerome Writing portrays the elderly saint deeply absorbed in his translation of the Bible. His thin, sinewy arm reaches out for ink, a detail that speaks to his focus and tireless intellectual labor. Before him rests a human skull, a stark reminder of death’s constant presence beside life.

Commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, this work stands out for its striking contrast between the warmly lit flesh tones and the cold darkness that surrounds them. This division of light intensifies the tension between two realms – life and death, wisdom and decay.

Though once dismissed as unfinished due to its rough, unpolished strokes, it is precisely this starkness that gives the painting its emotional depth, transforming it into a powerful meditation on mortality and the human condition.

References:

theartnewspaper.com

art-facts.com